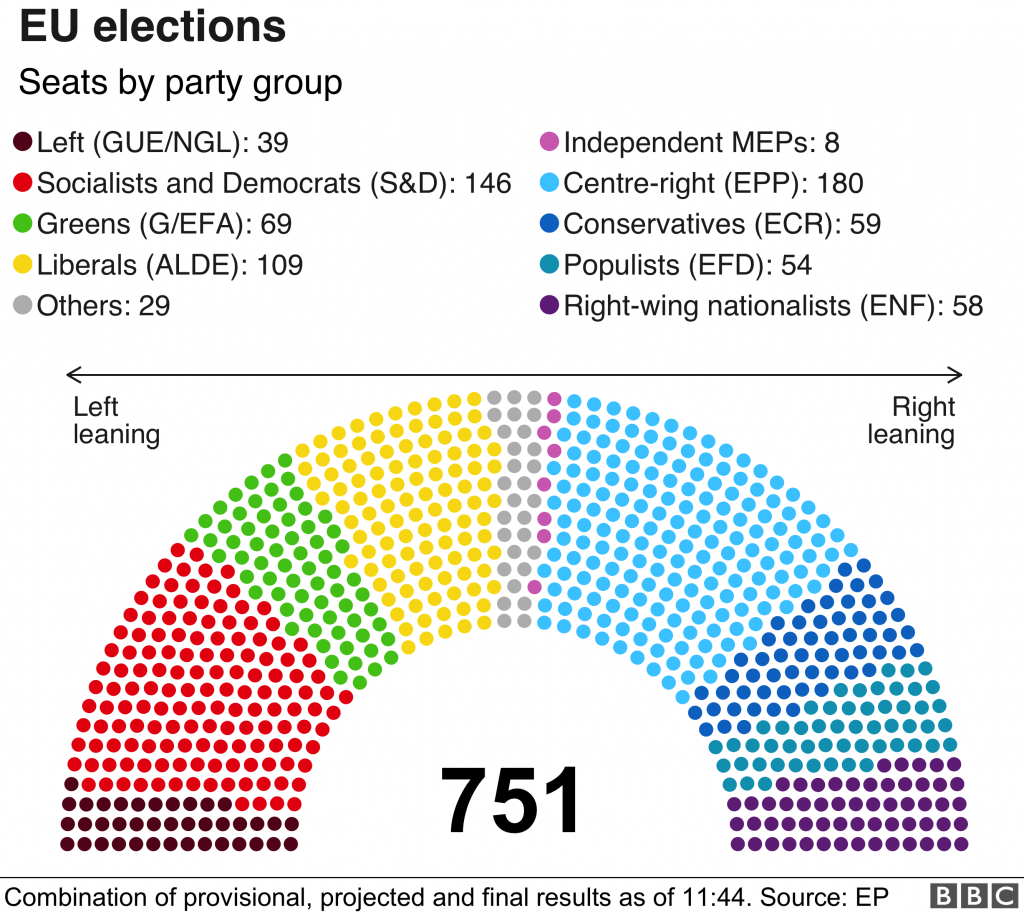

The big centre-right and centre-left blocs in the European Parliament have lost their combined majority amid an increase in support for liberals, the Greens and nationalists.

Pro-EU parties are still expected to be in a majority but the traditional blocs will need to seek new alliances.

The liberals and Greens had a good night, while nationalists were victorious in Italy, France and the UK.

Turnout was the highest for 20 years, bucking decades of decline.

Although populist and far-right parties gained ground in some countries, they fell short of the very significant gains some had predicted.

The centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) remains the largest bloc and analysts say it is likely to form a grand coalition with the Socialists and Democrats bloc, with support from liberals and the Greens.

In the UK, the newly-formed Brexit Party claimed a big victory, and a strong performance by the Liberal Democrats came amid massive losses for the Conservatives and Labour.

The European Parliament helps shape EU legislation and the results will play a big part in who gets the key jobs in the European Commission, the Union’s executive.

What do the results mean for the EU?

Based on current estimates, the previously dominant conservative EPP and Socialists and Democrats blocs will be unable to form a “grand coalition” in the EU parliament without support.

The EPP was projected to win 179 seats, down from 216 in 2014. The Socialists and Democrats looked set to drop to 150 seats from 191.

Pro-EU parties are still expected to hold a majority of seats however, largely due to gains made by the liberal ALDE bloc, and particularly a decision taken by the party of French President Emmanuel Macron to join the group. His Renaissance alliance was defeated by the far-right National Rally of Marine Le Pen.

“For the first time in 40 years, the two classical parties, socialists and conservatives, will no longer have a majority,” said Guy Verhofstadt, the leader of the ALDE.

“It’s clear this evening is a historical moment, because there will be a new balance of power in the European Parliament,” he said.

There were major successes for the Greens, with exit polls suggesting the group would jump from 50 to around 67 MEPs.

But gains for nationalist parties in Italy, France and elsewhere means a greater say for Eurosceptics who want to curb the EU’s powers.

Matteo Salvini, who leads Italy’s League party, has been working to establish an alliance of at least 12 parties, and his party set the tone winning more than 30% of the vote, according to partial results.

Beyond the status quo

This outcome reflects a tendency already apparent in national elections all over Europe: rejection of the status quo. Look at the beating meted out to France’s centre-right and centre-left, to Angela Merkel and her Social Democrat coalition partners, plus the slap in the face delivered to the UK’s Conservative and Labour parties.

Europe’s voters are looking elsewhere for answers. They’re drawn to parties and political personalities they feel better represent their values and priorities.

Some are attracted by the nationalist right, promising a crackdown on immigration and more power for national parliaments, rather than Brussels. Italy’s firebrand Deputy PM Matteo Salvini is a successful example, as is Hungary’s Viktor Orban.

Other voters prefer a pro-European alternative, like the Green Party and liberal groups. They also performed well in these elections.

Who were the winners and losers?

In Germany, both major centrist parties suffered. Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats dropped from 35% of the vote in 2014 to 28%, while the centre-left Social Democratic Union fell from 27% to 15.5%.

The right-wing populist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) performed worse than expected – projected in exit polls to win 10.5% – while still improving on its first results in 2014.

In the UK, the newly formed Brexit Party, led by Nigel Farage, secured about 32% of the vote, amid gains for the Liberal Democrats and significant losses for the Conservative and Labour parties.

Amid mixed results for far-right parties across Europe, Ms Le Pen’s National Rally party – formerly the National Front – was celebrating victory in France over Mr Macron’s party, securing 24% of the vote to his 22.5%.

A presidential official described the outcome as a “disappointment” but “absolutely honourable” compared to previous results.

In Hungary, Viktor Orban, whose anti-immigration Fidesz party took 52% of the vote and 13 of the country’s 21 seats, was also a big winner.

“We are small but we want to change Europe,” Mr Orban said. He described the elections as “the beginning of a new era against migration”.

In Spain, the ruling Socialist party (PSOE) took a clear lead with 32.8% of the vote and 20 seats, while the far-right Vox party won just 6.2% and three seats – coming in fifth.

In Greece, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras called for an early election after the opposition conservative New Democracy party won 33.5% of the votes to 20% for his Syriza party.

The right-wing ruling Law and Justice party did well in Poland, winning 45% of the vote, and 27 of the country’s 51 seats.

Why was the turnout so high?

EU citizens turned out to vote in the highest numbers for two decades, and significantly higher than the last elections in 2014, when fewer than 43% of eligible voters took part.

Turnout in Hungary and Poland more than doubled on the previous poll, and Denmark hit a record 63%.

Analysts attributed the high turnout to a range of factors including the rise of populist parties and increased climate change awareness.

How does the European Parliament work?

It is the European Union’s law-making body.

It’s made up of 751 members, called MEPs, who are directly elected by EU voters every five years. These MEPs – who sit in both Brussels and Strasbourg – represent the interests of citizens from the EU’s 28 member states.

One of the parliament’s main legislative roles is scrutinising and passing laws proposed by the European Commission – the bureaucratic arm of the EU.

It is also responsible for electing the president of the European Commission and approving the EU budget.

The parliament is comprised of eight main groups that sit together in the chamber based on their political and ideological affiliations.

Content is for general information purposes only. It is not investment advice or a solution to buy or sell securities. Opinions are the authors; not necessarily that of OANDA Business Information & Services, Inc. or any of its affiliates, subsidiaries, officers or directors. If you would like to reproduce or redistribute any of the content found on MarketPulse, an award winning forex, commodities and global indices analysis and news site service produced by OANDA Business Information & Services, Inc., please access the RSS feed or contact us at info@marketpulse.com. Visit https://www.marketpulse.com/ to find out more about the beat of the global markets. © 2023 OANDA Business Information & Services Inc.